The Total Party Kill (TPK) – Part 2

By

So your adventuring party went and got itself totally wiped out. It may have been through thrilling heroics and noble sacrifice or poor choices and bad dice rolls. But where do you, both as players and characters, go from there? In this edition, we’ll take a look at a few options, along with the pros and cons, when the adventuring group suffers the dreaded Total Party Kill.

Back Up Characters

Depending on the GM, some groups have players create two or more characters at the start of a campaign: their main character and a “backup” in case of their demise. Sometimes these backups are spitting images of the main characters, but they are often something completely different. Neither choice is wrong.

The GM, however, has to to decide if these characters are “included” in the storyline in some way. For example, a fighter (Player 1) could have a younger sister back home who is equally skilled in the sword. During the campaign, the player could occasionally visit his sibling, thus creating a chance for creating her personality and roleplaying potential. This works for keeping the narrative intact, but requires additional paperwork, as the backup character should be roughly the same level as the main one.

Having backup characters ready for the possibility of a TPK creates some interesting play dynamics. On one hand, your players know the GM is not going to fudge any dice rolls or secretly take it easy on the party. The players take more chances and delve into the drama of playing with the safety of backup characters in mind.

This concept can get pushed too far, however, with players that take outlandish chances or dive into suicidal situations because they have that backup character in mind. Even in games that are more “hack and slash”, the constant churn of new characters can get tedious. If you feel that players are taking advantage of their “unlimited lives” then LIMIT them—one, maybe two backup characters per player per campaign. If players are going through more character than that, then you might consider if this is the right style of game for your group.

Resurrection at the Table

Resurrection (or the classic raise dead spell) is a solid consideration, however it is totally dependant on a number of factors in the game. Is there a means within the storyline to effectively have the party resurrected? Does it maintain the suspension of disbelief?

Resurrection (or the classic raise dead spell) is a solid consideration, however it is totally dependant on a number of factors in the game. Is there a means within the storyline to effectively have the party resurrected? Does it maintain the suspension of disbelief?

Play style may also be a factor, it could be that the game is a much lighter environment, more like a “respawn” in an MMO. If this is the case, then the group might consider at least maintaining some larger drawback to offset the ease of resurrection. The loss of wealth, experience and/or both are classic examples of how that is handled in many game systems. As with most things, if there is no real threat (“I’ll just respawn”), the game could quickly become boring or repetitive.

One way around this is to make the very concept of returning from the dead a harrowing experience. If a character resurrects, in addition to XP loss, gold to cast the spell, and other mechanical costs, impose some roleplaying aspects—the character is haunted by ghostly voices, animals now shy away from him, or maybe his wounds never truly heal up, leaving him scarred and mutilated.

Storyline Implications

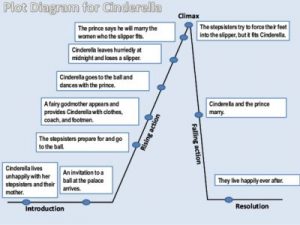

As a GM, the TPK can throw a serious monkey wrench in the works; recovering from one can be easy or very hard. In the diagram shown here, suppose Cinderella slipped running down the stairs, not only losing a slipper, but breaking her neck (critical fumble). The complexity of storyline recovery highly depends on game style, adventure architecture, and gaming experience.

As a GM, the TPK can throw a serious monkey wrench in the works; recovering from one can be easy or very hard. In the diagram shown here, suppose Cinderella slipped running down the stairs, not only losing a slipper, but breaking her neck (critical fumble). The complexity of storyline recovery highly depends on game style, adventure architecture, and gaming experience.

A group with a more cinematic gaming style may find it much easier to deal with a TPK in the story. The GM can readily resurrect the party or set another accommodation into the storyline. For example, while travelling the wasteland, a roaming caravan could find the adventurers—resurrect them, provide shelter, rest, and aid. After receiving such help, the party could then return to the main storyline.

A group with a more realistic game style may struggle to move forward after a TPK. In some cases, they may have no better option than to start fresh with new characters. However, even with realistic play, a dedicated group may find another way to continue the adventure. For instance, a GM might send a second group of adventurers to recover the fallen party and return them to a temple to have them resurrected.

Life, Death, Rebirth

For almost the same reasons above, the storyline architecture can severely limit the options available to the GM in handling a TPK. It is possible that the given situation within the story itself just does not have any means to allow for the party to return. For example, if Boromir had not found an inner strength to overcome the temptations of the ring and killed Frodo, the Orcs would have overrun the rest of the party, the ring lost and there wouldn’t really have been any chance of recovering the storyline.

For almost the same reasons above, the storyline architecture can severely limit the options available to the GM in handling a TPK. It is possible that the given situation within the story itself just does not have any means to allow for the party to return. For example, if Boromir had not found an inner strength to overcome the temptations of the ring and killed Frodo, the Orcs would have overrun the rest of the party, the ring lost and there wouldn’t really have been any chance of recovering the storyline.

For GMs, it’s important to begin a new campaign with an open, honest discussion about play styles and the possibilities of character death. If the campaign is designed to be intentionally brutal, let them know up front. Follow-through is important—check in with your players after a few play sessions (and maybe a couple of character deaths) to see if the style and lethality of play still works for your players. If it does, great. If not, it may be time to dial back the challenge level or even reconsider the overall style of play.

Players are just as responsible, accepting the “lethality level” of a campaign set at the beginning by the GM. Continual feedback is key; if the players don’t let the GM know that they are unhappy with having to rely on constant resurrections or backup players, then nothing will change.

In short, two-way communication and honesty is key for the gaming group to survive the Dreaded Total Party Kill. See the next article in this series, Moving Forward or “What did we learn from these events?”